Executive Summary

In the shadow of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the geopolitical situation in the South Caucasus region is changing. Azerbaijan is driving much of this change. While Baku has in effect ended the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh – leading to the displacement of the region’s Karabakh Armenians – there are many remaining obstacles to peace with Armenia.

The recent events have also spurred numerous geopolitical discussions in western capitals, such as the risk of regional military escalation, the implications for Russia’s influence in its neighbourhood, the changing dynamics of Eurasian geopolitics, and autocratic challenges to the rules-based order. Similarly, these developments have triggered difficult policy debates within the EU on its approach towards Azerbaijan and the region, as well as on the EU’s geopolitical ambitions and its capacity to simultaneously manage wars in three distinct theatres – Ukraine, the Middle East, and the South Caucasus.

In the current situation, Baku’s geopolitical situation and foreign policy are demarcated by two interconnected dimensions – uncertainty and room for manoeuvre. Azerbaijan faces many complex, entangled variables that both enable and restrict its goals and options. These involve: using its current strength to enforce its goals in its relations with Armenia; leveraging its growing regional power in its perilous relations with neighbours, Russia and Iran; capitalizing on and handling ties with both of its allies, Türkiye and Israel, at the same time, despite growing tensions between them in the Middle East; upholding crucial economic connections with the European Union while managing difficult political relations; and consolidating its emerging role as regional connectivity and energy hub. Baku must cautiously navigate between all of these.

As it is still unclear how Baku will act within this nexus of uncertainty and manoeuvrability, the EU’s policy towards Baku and the region must be strategic, careful and balanced. The EU has significant leverage over Azerbaijan but is also dependent on working relations with Baku. The EU’s policies on Azerbaijan, in conjunction with its approach to Armenia, must be integrated into a broader policy framework and holistic regional strategy for the South Caucasus. This would also align with the EU’s policies on the Eastern neighbourhood, as well as on Russia, Iran, Türkiye and Central Asia.

The EU must therefore engage strategically with both Azerbaijan and Armenia, designing and implementing policies proactively to reach its goals in the South Caucasus region. These include a stable, peaceful and prosperous Eastern neighbourhood, regional influence, to isolate and counter Russia, and improved connectivity and energy security.

The EU should provide support for Armenia while improving cooperation with Azerbaijan where possible and relevant. The EU must send clear messages to Baku on red lines for military action while communicating strategically to avoid alienating Baku and losing its credibility and position as a possible peace mediator. While cooperating with Baku on energy, connectivity and transit, the EU must ensure that this does not enable Russian sanctions evasion, and must continue to influence the country in the direction of European values, human rights, and democracy.

Introduction

In September 2023, in its so-called anti-terrorist military operation, Baku quickly recaptured the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which had been controlled by local Armenians since the First Karabakh war in the early 1990s, thereby ending the “unfinished business” from Baku’s victory in the Second Karabakh war in 2020. This led to the mass displacement of almost all of the region’s Armenian population, triggering a humanitarian crisis. However, questions remain regarding the next steps in the still-unfinished conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and whether peace and normalization are now more or less likely.

These events took place against the backdrop of a South Caucasus already in geopolitical turmoil as a result of: Azerbaijan’s growing military clout, backed up by its allies Türkiye and Israel; Armenia’s abandonment by its alleged security guarantor, Russia; Russia’s failing invasion of Ukraine and attempts to evade sanctions and global isolation; the increasingly ambitious presence in the region of other actors such as Türkiye and the EU; and tensions between Azerbaijan and Iran.

All this raises several further questions: Where is the region headed, in terms of conflicts, alliances, and cooperation? How are the power dynamics between the regional actors of Russia, Türkiye, Iran and the EU changing? How is Azerbaijan’s crucial role in this geopolitical interplay evolving?

Addressing these questions is important for many reasons that reach beyond Azerbaijan. The South Caucasus region is crucial to many actors for geopolitical, economic and security reasons. It is a central node in both North-South and East-West transit and energy routes. The South Caucasus also affects and is affected by other adjacent geopolitically vital regions – the greater Middle East, Central Asia, and the Black and Caspian seas. The region is especially important for the EU – including for its new-found geopolitical aspirations; for countering Russia; and for ensuring stability, peace and democracy in its Eastern neighbourhood.

This report therefore has several analytical goals: First, to elucidate the current complex geopolitical developments and dynamics in the South Caucasus region through the starting point of Azerbaijan’s position. Second, to provide a better understanding of Azerbaijan’s motives, actions, and prospects as the central actor in this geopolitical drama. Third, to examine how this is affected by, and affects, the shifting roles, influence, and interplay in the South Caucasus of its regional power players.

Section 1 deals with Azerbaijan’s relations and ongoing conflict with Armenia. Section 2 expands on Azerbaijan’s ties with allies and partners, notably Türkiye, Israel and the EU. Section 3 elaborates on Azerbaijan’s complex connections with its two capable neighbours and main geopolitical threats – Russia and Iran. The report concludes with a look ahead at what is to come for Azerbaijan and the South Caucasus, and what this means for EU policy.

Armenia: Conflict Resolution or Escalation on the Horizon?

Azerbaijan’s conflict-ridden relations with Armenia have long been centred on the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh. Baku has now seemingly de facto terminated this conflict and re-established its territorial integrity by achieving its political goals by military means. One question is why this happened now, while others include how this will affect the peace and normalization process with Yerevan and what comes next in their relations.

Why now? A military solution fuelled by frustration, worry and opportunism. Following its victory in the 2020 war and the Russian-brokered ceasefire, Azerbaijan, like Russia, had grown increasingly frustrated with perceived Armenian delays and deceptions: “They [Armenia] are bending over backward to include the Karabakh issue in a possible peace agreement and block it” (President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev, January 2023). At the same time, Baku was impatient to use the current window of opportunity provided by its strong position and the seeming possibility of extracting concessions from Armenia’s current leader – Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. Baku was probably also worried about potentially destabilizing developments that might threaten Azerbaijan’s consolidation of its war gains, such as the end of the five-year mandate in 2025 of the Russian peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh, and fluctuating tensions with Iran.

Moreover, the 2020 war taught Baku several vital lessons: that Azerbaijan’s military capacity was now decisively larger than Armenia’s; that Russia would not interfere with Baku’s military actions; that the West would not punish Azerbaijan with more than words; and that it was possible to reach political ends by military means. Thus, Baku’s decision might also partly have been driven by opportunism. As Aliyev pointed out in January 2023: “Because last year […] we have shown three times that no one can withstand us and we will achieve what we want”.

More directly, the events were likely catalyzed by several recent developments. These include the so-called ‘presidential elections’ held in Nagorno-Karabakh in September, which constituted a red line for Azerbaijan and were not recognized by the EU; and the numerous recent mine incidents resulting in Azerbaijani fatalities.

The Many Enduring Obstacles to Peace

However, despite the centrality of Nagorno-Karabakh, the conflict with Armenia is far from over. Many issues remain on the path to peace and normalization: Armenians fear Azerbaijani military action against Armenia; a peace agreement is yet to be signed; questions such as border demarcation, exclaves on both sides and the opening of regional trade routes are still outstanding; and the long-term fate of Karabakh Armenians is highly uncertain.

The prospects for reaching a peace agreement are difficult to assess as there have been both promising and more troubling developments. Positive signs include recent optimistic signals from both Armenia and Azerbaijan, for example from Pashinyan who in October expressed hope that “this process will successfully conclude in the coming months”. Negative signs include an increasing number of cancelled meetings.

The question of the status of Nagorno-Karabakh and its ethnic-Armenian population has always been the major hurdle, and with the territorial question de facto resolved peace might be closer. For Yerevan, Nagorno-Karabakh was also a very difficult problem, as it could not formally annex it for political reasons but was forced to sustain it, despite the economic and political burden this imposed on Armenia. One important consideration is the very different political outlooks, strategies and priorities of Armenians in Armenia, Karabakh Armenians and the more radicalized parts of the Armenian diaspora.

Another issue is the choice of peace track through which to progress, where the sides have differing views. With minimal trust in Russia and the Minsk Group no longer relevant, both sides probably still see the EU as the more honest and desirable broker – perhaps also because of its feebleness. However, while Armenia is increasingly positive about Western participation, the view in Baku is that French participation constantly derails the process. In October 2023, Aliyev stressed that “if any new conflict occurs in the region, France would be responsible for causing it”. Moreover, recent EU-Azerbaijani tensions related to Baku’s reaction to EU (mainly French) actions and rhetoric have endangered the EU’s role as mediator.

Thus, in Baku’s view, Turkish involvement is needed as a counterbalance, which is difficult for Yerevan to accept. Moreover, the regional 3+3 format, which includes Georgia (although Tbilisi missed the latest meeting), and the three major regional powers of Russia, Türkiye and Iran, has also seen some activity recently. Another recently suggested option is the intra-regional Georgia track, although how viable it is without a third extra-regional party remains to be seen.

Importantly, the power to mediate means power to influence, which Moscow clearly demonstrated after the first and second Karabakh wars. However, since the resolution of the 2020 war, in which Moscow came out on top as peace mediator, Russia has seen its mediation dominance challenged by the West. Thus, the ongoing parallel efforts in different peace tracks reflect competition for authority between the EU and the US, on the one hand, and Russia and to some extent Türkiye and Iran, on the other. Moscow and Tehran in particular view Western involvement in peace mediation as encroaching on their interests in the region, and as “harmful to regional peace and stability”, according to Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi. Meanwhile, both Baku and Yerevan take political advantage of this situation vis-à-vis the different actors by simultaneously utilizing and leveraging different mediation formats.

A major outstanding issue is the fate of the Karabakh Armenians, and whether they will be able and willing to return to Nagorno-Karabakh or not. Several potential scenarios are conceivable, ranging from the status quo to a temporary or small-scale return to a more widespread and permanent return. The last would require far more trust from both sides and overcoming many obstacles: the lack of credible Azerbaijani commitments to ensuring their safety and rights; the Armenian rhetoric on Azerbaijan, which fuels the Karabakh Armenians’ fears; and a long history of large-scale human rights violations by both sides. This sensitive issue has consistently been one of the most difficult to parse in negotiations.

Finally, the long-term stability and sustainability of the current status quo builds on many assumptions that could prove precarious in the years to come. One is whether the superior military and economic capacity of Azerbaijan will last. Here, there is Armenian hope for a change in the power balance, brought about, for example, by future diminishing oil and gas revenues for Azerbaijan, or an increase in Armenia’s military support from the US, Iran, France or India.

Image 1: Azerbaijan and Armenia. Image: Golden. License. Changes made: “Nakhchivan” and “Syunik” captions added; colour coding of Armenia changed.

Further Military Escalation: The Zangezur Corridor?

In the current uncertain and potentially volatile situation, Armenia fears potential further military aggression by Azerbaijan against Armenia itself. These fears concern Armenia’s southern Syunik province, and especially the hypothetical so-called (by Azerbaijan and Türkiye) Zangezur corridor,[1] which would be an extraterritorial strip of land running from southern Azerbaijan through Armenia along its border with Iran to Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan exclave. The corridor is part of regional transport links to be unblocked, and controlled by Russian border guards, according to the 2020 November trilateral ceasefire statement. Armenia fears that Azerbaijan might open this corridor by force, and in theory the corridor could be controlled by Azerbaijan, Türkiye, Russia or a combination of the three. Apprehension over the security of Syunik is shared by the West, Iran and Russia, all of which have recently increased their involvement and presence in the province.

There are several arguments for why Azerbaijan might in the current situation or the near future consider military operations in Armenia, such as creating the Zangezur corridor by force or to recapture eight Azerbaijani villages currently under Armenian control. First, Azerbaijan is in a much stronger military and political position vis-à-vis the weak and vulnerable Armenia. Thus, Azerbaijan in theory could if it wanted to. Second, Azerbaijan has repeatedly shown a willingness to use military force to reach its political goals. Third, Azerbaijan might draw the same conclusions from September 2023 as it did from the 2020 war: that outside forces will not stop or seriously punish its military endeavours.[2]

Finally, Azerbaijan (and Turkiye) continue to use threatening rhetoric and actions against Armenia, including the irredentist “western Azerbaijan” term for southern Armenian territories, and carried out joint Turkish-Azerbaijani drills near Armenia’s borders in October 2023. Thus, Baku in many ways treats Yerevan as a defeated enemy rather than an equal to make peace with. One clear example of this is Aliyev’s October visit to and speech in Khankendi[3] in Nagorno-Karabakh: “If some forces in Armenia ever think about revenge, let them take a good look at these images”.

On the other hand, there are also many reasons why Azerbaijan might be reluctant or unwilling to use military force against Armenia. First, the goal of retaking Nagorno-Karabakh has been unmatched by any other political aim in Azerbaijan’s foreign or domestic politics in the past three decades, which means drawing conclusions from this is risky. Second, the idea of the Zangezur corridor was probably used by Azerbaijan as a way to counterbalance the issue of the Lachin-corridor to Nagorno-Karabakh. Third, resolving Nagorno-Karabakh was politically urgent for Baku given the current window of opportunity, whereas the goal now is probably to consolidate its gains. Fourth, sub-optimal but functioning alternatives exist for Azerbaijan, which is now working with Iran on a new, shorter trans-Iranian corridor to Nakhchivan. This would also serve the purpose of partly isolating Armenia.

Finally, and crucially, unlike retaking Nagorno-Karabakh, it is highly questionable whether such military endeavours are in Azerbaijan’s interests, given the likely high economic, military and political costs. These include potential military conflict with Iran (see section 3), the risk of regional economic disruption and greater regional escalation, grave reputational damage internationally and much worsened relations with the West, including negative consequences for Azerbaijani energy exports (and even potential sanctions, although unlikely). It would also severely damage the peace process and might cause social unrest at home.

Moreover, while Azerbaijan’s repeated and clear statements that it has no intention of attacking Armenia might be mainly intended to soothe a western audience, and might lack credibility given Baku’s similar previous promises, they could also be a genuine reflection of current circumstances for Baku. At the same time, it is important to differentiate between Zangezur corridor plans and other potential military action and escalation scenarios.

Finally, Azerbaijan is not the only actor with a stake in a potential Zangezur corridor, as both Russia and Türkiye have expressed an interest in this and would benefit from it for transit reasons. Whether Ankara or Moscow would take the lead in such a project is a much more difficult question. Russia has repeatedly publicly opposed the idea of an extraterritorial corridor, and instead frequently stated that its Federal Security Service (FSB) should monitor any transport link between Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan – in line with the trilateral statement – which has led to angry Armenian rebuttals. This ongoing conflict between Moscow and Yerevan is also a reason why Russia was and is less inclined to oppose Azerbaijan’s actions.

Ankara would benefit economically and politically from a direct trade route with Azerbaijan proper in addition to bordering Nakhchivan, and a potential gateway to the Turkic states of Central Asia – in line with Ankara’s pan-Turkish ambitions. However, Ankara has also tried to balance this with rhetorical efforts to alleviate Tehran’s fears about the Zangezur corridor (see section 3).

A Motley Mix of Allies and Partners

Azerbaijan’s rising star is to a significant extent linked to its growing relations with allies and partners, among which Türkiye, Russia (see section 3) and Israel are the most important. Another important partner for Azerbaijan, at least in the economic arena, is the EU – Azerbaijan’s number one trading partner for the past five years.[4] Azerbaijan is also striving to increase cooperation with Central Asian countries on connectivity, transit and energy, and to boost and utilize its significant soft power.

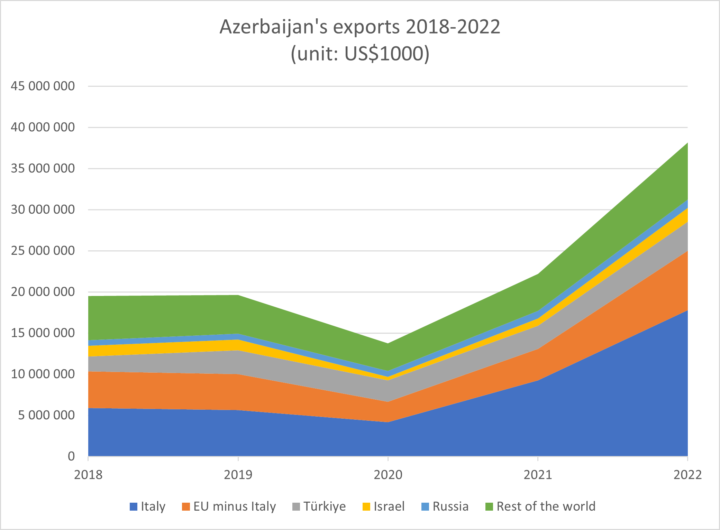

Figure 1: Azerbaijan’s total exports 2018-2022. Source: UN Comtrade database, Azerbaijan reporting. Note: Does not accurately reflect the big increase in natural gas exports in 2022.

Türkiye: The Brotherly Military Duo With Wider Aspirations

Türkiye is Azerbaijan’s closest political and military ally. As fellow Turkic-ethnic states, the two countries share cultural, historical[5] and linguistic ties, have strong political relations that have been growing for many years, and frequently describe each other as brotherly nations, or as “one nation, two states”, for example by President of Türkiye Recep Tayyip Erdogan in September 2023.

In the economic sphere, Türkiye is a moderately important trading partner, which accounts for 14% of Azerbaijan’s imports and 12% of its exports, behind Russia and the EU. Importantly, Ankara and Baku have a strategic infrastructure cooperation in the energy and rail sectors, as Azerbaijani gas and oil exports to both the EU and Israel pass through Türkiye.

Türkiye’s greatest importance for Azerbaijan is linked to its military support. While it is only a minor source of Azerbaijan’s total arms imports – 2.9% in 2011–2020 – Türkiye has supplied Azerbaijan with some of its most critical military equipment, including the Bayraktar drone. Moreover, Türkiye has provided extensive military backing to Azerbaijan in various ways for three decades. In Azerbaijan’s long conflict with Armenia, Türkiye has been Azerbaijan’s most ardent political backer from the beginning, most recently in Baku’s recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh. In the 2020 war, Ankara’s military support – including by providing drones and military advisory personnel – played a decisive role in Baku’s victory.

Crucially, the countries have enjoyed close and continuous military cooperation and coordination since the early 1990s, especially in the training of Azerbaijani officers, military exercises and military technology sharing. This has been paramount for the combat capacity of Azerbaijan’s army, as Aliyev stated in June 2023 that a main goal has been to allow it to transition into a modern army “on the basis of the Turkish model”. The two countries are striving for interoperability, including through increased Turkish presence in and integration into Azerbaijan’s army.

In June 2021, the two countries signed the Shusha Declaration on Allied Relations, which formally raised the relationship from a strategic partnership to an alliance. In December 2022, the then-Turkish defence minister, Hulusi Akar, emphasized that: “No matter where the threat or the provocation comes from, we know how to be a single military, a single power and a single fist with Azerbaijan”. A central cooperation component for many years has been joint drills, such as in Azerbaijan in October 2023, including in Nagorno-Karabakh. These also serve the purpose of power projection and geopolitical signalling vis-à-vis Yerevan, Moscow and Tehran, as was the case with the drills near the Azerbaijani-Iranian border in December 2022.

Türkiye, for its part, has much to gain from its alliance with Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani gas is key to Türkiye’s energy security, and Azerbaijan’s state oil and gas company, SOCAR, is the biggest foreign direct investor in Türkiye. Through Baku, Ankara is also helped to manage its difficult relations with Tel Aviv (see below). Moreover, support for Azerbaijan has strong public support in Türkiye.

Importantly, through its alliance with Azerbaijan – and due to Baku’s ascendancy and military victories in 2020 and 2023 – Türkiye’s geopolitical weight in the South Caucasus has increased, especially since the 2020 war, in relation to its two partners and rivals Russia and Iran. Through its position in the South Caucasus, Ankara has also gained leverage over Moscow in the power balance in the Middle East, which includes Syria and Libya. Moreover, as Yerevan and Baku move closer to peace, normalization between Ankara and Yerevan becomes more likely, which is also in Türkiye’s interests.

Figure 2: Azerbaijan’s total imports, 2018–2022. Source: UN Comtrade database; Azerbaijan reporting.

Israel: An Oil- And Weapon-Fuelled Joint Front Against the Iranian Threat

Israel is another vital military ally and political backer for Azerbaijan. Like Türkiye, Israel was one of the first countries to recognize Azerbaijan’s independence in 1991, and it has had an embassy in Baku since 1992. Political ties have grown significantly in recent years, as exemplified by the appointment in January 2023 of Azerbaijan’s first ambassador to Israel; the visit to Azerbaijan of Israel’s defence minister in July 2023; and cooperation on the establishment of an Azerbaijan Cyber Security Centre in March 2023. In his first visit to Azerbaijan in May 2023, President of Israel Isaac Herzog asserted that the relationship: “is not just Iran and defense; it’s also about trade, tourism and energy”.

A central aspect of the strategic partnership between Azerbaijan and Israel is joint efforts to counter and contain Iran. For both Azerbaijan and Israel, Iran is a highly dangerous military and hybrid threat, and central to their foreign, security and defence policies. Thus, through their military and security cooperation, both can improve their strategic positions and deterrence vis-à-vis Tehran, and counter Iran’s regional sway. For Israel, getting closer to Iranian territory from the north through its presence in Azerbaijan has many offensive and defensive benefits for military and intelligence purposes.

Israel is an extremely important source of weapons for Azerbaijan. Tel Aviv’s arms exports to Baku have been fundamental to building up Azerbaijan’s military capacity for many years – at least since the mid-2000s, but particularly since the 2010s. In the decade 2011–2020, Israel supplied 27% of Azerbaijan’s arms imports. While Russia was Azerbaijan’s top supplier over the same period, Israel’s share has been increasing steadily over time. In 2013-2017, 30% of Azerbaijan’s arms imports were from Israel, but by 2015-2019 the proportion had risen to 60%, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). In 2016, Aliyev claimed that Azerbaijan had bought Israeli weapons worth US$5 billion.

Thus, Tel Aviv’s military support to Baku has been crucial in Azerbaijan’s conflict with Armenia, including victory in the 2020 war and afterwards, involving arms such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), loitering munitions, guided missiles and ballistic missiles. Moreover, Israel also shares military technology with Azerbaijan through the presence of Israeli companies and joint arms production on Azerbaijani territory. In 2018–2022, Azerbaijan was Israel’s second largest arms export partner after India, receiving 9% of Israel’s total arms exports.

Furthermore, Azerbaijan’s ties with Israel are important for Baku’s frequent narrational efforts to portray itself as a multicultural and multi-religious state that provides for and ensures the rights of its minorities. This is also connected to the conflict with Armenia on what rights Karabakh Armenians would have as citizens of Azerbaijan. Speaking of Azerbaijan’s Jewish community in September 2023, Aliyev proclaimed that a “high culture of coexistence, exemplary friendship and fraternal relations between representatives of different peoples and religions reigns in Azerbaijan”. Azerbaijan has also benefited from lobbying efforts by pro-Israel forces in the US.

For Tel Aviv, Baku is a vital energy partner, as around 40% of Israel’s oil is supplied by Azerbaijan. Importantly, this oil travels through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline and is then shipped from Türkiye to Israel, reflecting the role of Ankara in this relationship. Azerbaijan also serves as a bridge between Israel and Türkiye, as Baku has sought to support the strengthening of ties between Tel Aviv and Ankara.

The EU: Growing Energy Ties, Political Difficulties and Mutual Dependence

Azerbaijan’s relations with the EU can be summarized as economically stable, important and growing, but politically and strategically complex.

Economic Relations: Strong, Growing and Built on Azerbaijan’s Energy Exports

In the economic sphere, connections are strong and growing, but imbalanced as Azerbaijan exports much more to the EU than it imports from it. Crucially, the EU is Azerbaijan’s top trading partner, accounting for around 52% of Azerbaijan’s total trade in 2022.[6] Figures 1 and 2 show that the EU is Azerbaijan’s number one export partner, representing around 60% of Azerbaijan’s total exports in 2018–2022; and number one import partner, representing 18% of Azerbaijan’s total imports in 2018–2022, albeit surpassed by Russia in 2022.

On the export side, the EU is an extremely important destination for Azerbaijani exports, mainly of crude oil and natural gas which accounted for exports worth about €31 billion in 2022. Azerbaijan’s top EU export partners are Italy, Greece, Spain, Croatia, Czechia, Portugal and Germany. On the import side, the EU plays a less dominant role and imports are more evenly spread by both exporting country and especially type of goods.[7]

Importantly, as the EU has sought to replace sanctioned Russian oil and gas with Azerbaijani alternatives, relations at the highest political and strategic levels have grown considerably. In July 2022, while signing a Memorandum of Understanding on increasing Azerbaijani gas exports to the EU from 8 to 20 billion cubic metres (bcm) annually by 2027, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised the EU’s growing strategic partnership with Azerbaijan, naming Baku as one of the EU’s “reliable, trustworthy partners”. As Azerbaijan’s gas exports to the EU skyrocketed in 2022, many EU member states now depend on its gas, such as Italy, Hungary, Austria, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Romania, although Azerbaijan’s gas supply accounted for only 3.4% of total EU gas imports in 2022. This has led to strong criticisms from human rights groups regarding Azerbaijan’s internal repression.

However, Azerbaijan has also recently increased its trade cooperation with Russia, more specifically on the export of Russian gas and oil to Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan is struggling with limited infrastructure capacity and rising domestic demand, and has seemingly resorted to Russian gas to fulfil its gas export obligations to the EU. Moreover, there are continuing problems with ensuring investments and commitment from EU buyers in the envisaged increase in Azerbaijani gas export to the EU.

Political Ties: Stable but Complicated, With Mutual Dependency and Frustration

Importantly, the EU needs to have a good working relationship with Baku in order to reach many of its strategic goals in the South Caucasus region: peace and normalization between Azerbaijan and Armenia; pushing back against Russian clout and bolstering its own; improving the stability, prosperity and security of its Eastern neighbourhood; and building its stakes in this crucial hub of the East-West transit “Middle Corridor”. Moreover, and crucially, decreased Russian supremacy in the region does not automatically translate into EU influence, as Moscow’s repositioning and the ongoing Baku-Moscow cooperation demonstrate, and could instead only result in increased Turkish sway.

At the same time, the EU has considerable leverage vis-à-vis Baku. First, Azerbaijan is highly dependent on trade with the EU. Second, Baku probably needs the EU in order to make further progress in peace and normalization with Yerevan. Third, growing European weight in the South Caucasus means that it is in Baku’s strategic interests to continue to build constructive ties with the EU. Fourth, Azerbaijan does not simply want to be a gas station or railway for the EU, but instead wants more EU involvement and cooperation in the region and in Azerbaijan, including in areas such as demining, rehabilitation and renewable energy, among other things. Finally, many people in Azerbaijan would say that Azerbaijan is part of Europe.

Given this mutual dependency, the EU is therefore trying to strike a balance in its relations with Baku between improving economic, political and strategic ties, while at the same time criticizing and pressuring Baku for both its rhetoric and its actions vis-à-vis Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, and for its authoritarian governance and internal repression. Another challenge is the fate of the Karabakh Armenians, and the related clashing principles of international law that are central to the conflict –territorial integrity versus the right to self-determination.

However, this balancing act is far from plain sailing for several reasons. First, Azerbaijan (like Armenia) plays both sides at the same time, trying to manage and maximize benefits from relations with both Russia and the West. Baku often punishes the EU when it feels alienated by EU accusations by moving towards Moscow. Second, Baku often reacts harshly both to EU (and US) criticism and to EU support for Armenia, as highlighted by a November 2023 statement by Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the EU’s apparent support for Armenia and threatening rhetoric against Azerbaijan were clear examples of its biased policy and double standards.

Third, the EU institutions and member states often take “siloed approaches” to Baku. President von der Leyen has talked of Azerbaijan as a strategic partner and European Council President Michel has considerable credibility in Azerbaijan as a peace mediator, while High Representative and Vice President Josep Borell often talks tough, as in November 2023: “Our message to Azerbaijan is clear: any violation of Armenia’s territorial integrity is unacceptable and will have severe consequences for the quality of our relations”. Similarly, many EU member states have important gas deals with Azerbaijan, while France is a strong backer of Armenia and perceived extremely negatively in Baku. Moreover, the lobbying of both Azerbaijan and Armenia prevents united EU and member state views on the conflict.

Thus, in the EU there is both internal disunity and a general wariness of antagonizing Azerbaijan too much. The EU’s response to Azerbaijan’s recent military actions in Nagorno-Karabakh has thus largely consisted of statements and support for Armenia, despite talk of harsher measures. Looking ahead, three main questions arise: How resolutely would the EU react to large-scale Azerbaijani military aggression on Armenian territory? Has the EU succeeded in clearly signalling this as a clear red line? Is this enough to influence such a development?

Dangerous Neighbours North and South

Azerbaijan’s two most intricate relationships are with Russia to the north and Iran to the south. Squeezed between these two large, capable and partly antagonistic major regional powers, Baku must inevitably manage ties with Moscow and Tehran in a fluctuating balance between cooperation, competition, and deterrence. Furthermore, its territory and people have for most of the past millennium been part of either the Russian or the Persian empires, so Azerbaijan shares deep but thorny historical, cultural and political ties with both, and each considers Azerbaijan to be part of its ‘rightful’ sphere of influence.

Moscow’s and Tehran’s multifaceted and potent political, military and hybrid instruments are a constant source of worry and uncertainty for Baku. The internal situation in Azerbaijan is also salient here, as both Russia and Iran use various tools to both foment and take advantage of any destabilizing internal developments, be they political, socio-economical or religious. In Baku’s mindset, any show of weakness is likely to be seized on by Russia and Iran.

Thus, Baku exercises constant vigilance in a careful balancing act with Moscow and Tehran to ensure its security and its long-term foreign policy goals. Here, its two key allies in Ankara and Tel Aviv are instrumental in deterrence. However, this means that the evolving strategic, military and economic collaboration between Russia and Iran is a potentially worrying development.

Despite competition, rivalry and tensions, the three countries have an expanding strategic partnership in the transit, logistics and energy sectors. For Moscow and Tehran, this is indispensable to their efforts to evade sanctions and avoid isolation in their strategic struggle with the West. For Baku, this is a way to capitalize on its emerging position as a trading hub, and to manage relations with its threatening neighbours. Moreover, the trio are also working together in regional cooperation, such as the 3+3 format, which has the direct goal of keeping Western powers out. Russia has also played a role in mediating the fluctuating tensions between Baku and Tehran.

Russia – The Second-Best Friend and Second-Worst Enemy

Moscow has several aims in its partnership with Baku: to preserve its control as the regional hegemon; to counteract its international isolation and Western sanctions through trade ties and transit corridors; to bolster its relations with partners beyond Azerbaijan, such as Iran, Türkiye and India; and to push back against increasing western meddling in the region.

Baku’s aims for the relationship are to carefully navigate between maintaining crucial political and economic ties with Russia while also increasing its own power and independence in the region and pursuing foreign policy goals that often run counter to Russia’s interests. The two countries have seen both increased cooperation and increased tensions in recent years. Crucially, the two countries are closer politically than economically.

Economic Relations

Russia plays a moderate role in Azerbaijan’s foreign trade. Figures 1 and 2 show that Azerbaijan is not heavily dependent on Russia for imports (18% of total imports 2018–2022, mainly wheat, fat and oils, and prepared foodstuffs) or exports (4% of total exports 2018–2022, mainly fruits and nuts, vegetables and plastics). Importantly, Russia plays a much larger role in Armenia’s economy.

Figure 3: Azerbaijan’s trade turnover with Russia, 2018–2022. Source: UN Comtrade database; Azerbaijan reporting.

Moreover, trade increased only moderately in 2022 compared to 2021. Imports grew by 32% and exports by 6%. These statistics are crucial to discussions on how, and through which countries, Russia is circumventing western sanctions. They can be compared with growth in 2022 compared to 2021 in other post-Soviet countries’ trade with Russia, such as Armenia (exports up 198%; imports up 47%), Georgia (exports up 5%; imports up 79%), and Kazakhstan (exports up 25%, imports down 1%).

Importantly, however, Russia is one of Azerbaijan’s most important arms suppliers, providing 60% of Azerbaijan’s arms imports in 2011–2020 (and 94% of Armenia’s in the same period). These supplies include armoured vehicles, air defence systems, helicopters, artillery and tanks, among other things.

Political Relations

In the political sphere, Moscow and Baku are pursuing a balanced approach towards each other, reflecting the complexity of relations. One important factor is that both are consolidated autocracies, which allows for greater understanding between fellow autocrats Putin and Aliyev. It also leads to more commonalities in policy goals, such as regime survival, and maximizing power at home and abroad; methods, for instance, rallying the people around nationalism, repression of the political opposition and civil society and use of military means to reach political goals; and worldview, or a world order built on military might rather than rules-based liberal values.

In general, both political links and alignment have been growing since Azerbaijan’s victory in the 2020 war. The outcome of the war gave Russia a strong boost in its regional influence, as both peace mediator – as co-signatory to the trilateral peace agreement – and peacekeeper through its peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh. Since then, there have been frequent signs of increased cooperation and coordination. Interestingly, two days before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the countries’ presidents signed a broad political-military agreement, which was hailed by Aliyev as taking “relations to the level of an alliance”.[8]

Moreover, as Russia has opted not to provide any security assistance to Armenia or Karabakh Armenians to protect them from Azerbaijani military action, Armenia has grown rapidly and strongly anti-Russian in both words and actions, reflecting Armenia’s immense feelings of betrayal. Against this background, Moscow has in turn increasingly taken up anti-Armenian and pro-Azerbaijani stances in relation to the conflict and its resolution. Nonetheless, Russia’s economic dominance in Armenia remains intact and is increasing. Thus, while Russian-Armenian political links deteriorate, economic cooperation grows. Moreover, and crucially, Armenia remains militarily allied with Russia through two layers: both bilaterally and through the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), although Armenia’s participation in the latter is frozen.[9]

All this does not preclude the continued existence of tensions between Moscow and Baku. Verbal tensions between the countries continue, including frequent examples of threatening Russian rhetoric and angry Azerbaijani pushback. The reasons for friction include Baku’s dissatisfaction with Russian statements on Nagorno-Karabakh, displeasure with Russia’s use of destabilizing political tools and lack of trust in Russia as a peace mediator.

The Russian peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh, stationed there as part of the ceasefire agreement following the 2020 war, are an important factor in Russian-Azerbaijani ties. As with the Russian military presence in other post-Soviet states,[10] this serves as a tool to boost Moscow’s malign leverage. (Russia is the only regional power with its own deployed military units.) Baku has therefore been reluctant to see their contracted presence renewed after its expiration in 2025. Since Baku’s recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh, however, their future presence is uncertain, and they have seemingly started to withdraw.

The Effects of Russia’s War on Ukraine

Russia’s war on Ukraine has had both negative and positive impacts on Azerbaijan. On the one hand, the war has led to economic volatility and inflation, negative social impact, and increased regional instability and geopolitical insecurity. There has also been a negative impact on Azerbaijan’s trade relations with Russia, which is currently Azerbaijan’s number one import partner, and led to fewer remittances from Russia.

On the other hand, the war has also meant higher energy prices and therefore revenues for Azerbaijan. More importantly, a weaker, isolated and distracted Russia has given rise to new regional circumstances and possibilities for Türkiye’s, Iran’s and Azerbaijan’s international power projection and activities. Without a weaker Russia, less capable of asserting its dominance, developments around Nagorno-Karabakh might have been very different.

Importantly, in line with its balancing act versus Russia, Azerbaijan has provided Ukraine with political,[11] humanitarian and even military support during the war, which has elicited Russian anger and threatening rhetoric. Azerbaijan, however, has not been willing to support any of the six UN resolutions against Russia, demonstrating the balance Baku is trying to strike to avoid provoking Moscow too much.

Despite Russia’s weakness, however, Moscow’s many potent levers of control in the region remain. It is important to differentiate between Russia’s diminishing soft power and political influence and its many remaining tools – military, hybrid, political, economic and cultural. Thus, Russia’s ability to sabotage, destabilize, and sow and exploit chaos in the region is not necessarily diminished by developments in Ukraine. Moreover, as the South Caucasus is seen by Moscow as one of its most important regions of influence, it is reasonable to worry that Russia might and could seek to compensate there for its failures in Ukraine.

Furthermore, assessing whether Russia’s reduced regional influence is merely a brief interruption or a lasting shift on a longer timeline is complex. Russia is clearly not withdrawing from the South Caucasus, nor is it abandoning its objectives. Instead, it is regrouping, repositioning and shifting its focus among partners and methods. This includes maintaining and exploiting economic and military dominance in Armenia, intensifying pressure on Georgia, and cultivating political and connectivity relations with Azerbaijan, Iran and Türkiye.

Increasing Alignment or Shifting Power Balance?

Two crucial questions for understanding the region’s geopolitical developments and Azerbaijan’s role in them are the extent to which Baku and Moscow are aligned in their interests and how the current power dynamic between them is evolving.

There are several good arguments that Azerbaijan and Russia increasingly share several regional interests. These include joint hostility towards western support for and cooperation with Armenia, including Russia’s wish to punish Armenia for its pro-western turn; and increasing cooperation on regional both North-South, and East-West trade and transit routes, including in a quartet with Türkiye and Iran. Baku also continues to express appreciation of Russian peace mediation efforts, as Aliyev asserted in October 2023: “We perceive the mediation of the Russian Federation with gratitude because Russia is our neighbor and ally, as well as Armenia’s ally”.

However, the narrative about increasing “alignment” between Baku and Moscow is not entirely correct. The power balance in the South Caucasus is shifting, such that Russia increasingly needs Azerbaijan, while Baku’s room for manoeuvre is expanding. Russia is now more dependent on Azerbaijan (and Türkiye) for many of its main objectives in the region: to maintain its regional presence, transit possibilities and to push back the encroaching West, as well as slowing down the internationalization of the South Caucasus. Russian senior officials frequently visit Azerbaijan and highlight these concerns. According to Foreign Minister of Russia Sergey Lavrov in February 2023: “[…] interaction in this region, with the proactive involvement of Russia and Azerbaijan, is highly promising”.

Thus, Russian-Azerbaijani alignment is more of a passive convergence of interests driven by Russian weakness, acquiescence and opportunism, rather than masterful Moscow machinations or an active strategic alignment. Russia had little choice but to permit Azerbaijan’s military actions, even if the long-term results are probably detrimental to Russia’s regional clout.

However, the deepening confluence of priorities means that cooperation and coordination are likely to continue to increase, especially in the two emerging regional triads of mutual self-interest: Russia-Azerbaijan-Türkiye, and Russia-Azerbaijan-Iran. Crucially, Russia’s status and role in the region is thus steadily shrinking from regional hegemon to a transit partner building stakes in Azerbaijani-Turkish trade and connectivity.

Moreover, many argue that Moscow’s acquiescence to Baku finally “resolving” the protracted conflict demonstrates that Russia has abandoned its ubiquitous geopolitical instrumentalization of post-Soviet frozen conflicts as it shifts its foreign policy priorities. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, however, this line of reasoning is inadequate and partly mistaken, both as Russia’s choices were severely limited, and because Baku’s actions were in line with Moscow’s desire to punish Yerevan’s pro-Western turn and feet-dragging.

There are also many central issues where Russian and Azerbaijani interests fundamentally clash, restricting the potential room for alignment. First, Baku clearly realizes that it is in its strategic, economic, and geopolitical interests to reduce Russian leverage in Azerbaijan and the South Caucasus, as this means more clout and room for manoeuvre for Baku. This would provide more opportunities to improve beneficial ties with the West, which naturally runs counter to Moscow’s interests.

Second, Moscow and Baku have partially divergent views on Armenia’s current leadership. Both harbour deep mistrusts towards Yerevan and agree that Armenia has been obstructive in implementing previous agreements. However, for Moscow, the pro-western Pashinyan is someone who must be coerced, or replaced, to preserve Russian domination. For Baku, on the other hand, Pashinyan is useful as he more easily can be forced to cooperate and make concessions than his predecessors and potential alternatives. Additionally, the more pro-Western direction of his rule means less Russian sway in both Armenia and the region overall. Furthermore, Azerbaijan could benefit from a more western-oriented Armenia if it leads to increased Western influence on Yerevan, encouraging compromise and normalization of relations with Baku. However, this depends on the direction of the EU’s policies towards Armenia.

Third, achieving peace and normalization between Azerbaijan and Armenia aligns far more with Baku’s interests than with Moscow’s. Peace would allow Azerbaijan’s economic development but would deprive Russia of one of its main levers and hybrid tools in the region – the potential to destabilize, divide and conquer. Furthermore, despite recent tensions and Baku’s many misgivings, Azerbaijan probably still recognizes that the EU is by far the more honest peace broker than Russia.

Thus, the worst possible scenario for Russia is a continuation of the current status quo, where Azerbaijan holds on to Nagorno-Karabakh, Pashinyan holds on to power, and the EU continues its role in peace mediation.

Iran: Friction and Thaw With the Civilizational Foe

Azerbaijan has a complex, volatile and fluctuating relationship with Iran, marked by both tensions and mutual mistrust. Several aspects underlie this contentiousness, notably the pro-Turkish cultural policies of Azerbaijan that compete with Iranian influence; a difficult internal political situation in Iran, with different camps advocating different policies on Azerbaijan; and Tehran’s grievances with Azerbaijan’s strong secular identity,[12] despite the fact that it, like Iran, is a majority Shia Muslim country.

The issue which is fundamental both to the tensions, and Iran’s stance, is the very large Azerbaijani minority of up to 20 million people or more in northern Iran with latent secessionist ideas.[13] (This area is known by many Azerbaijanis by the irredentist term “Southern Azerbaijan”.) The latter is an extremely sensitive question for Iran given its worries about territorial integrity and separatism. Whenever tensions rise, Baku foments nationalist and secessionist ideas and actors related to the Iranian Azerbaijanis.

The complex dynamics of the South Caucasus create difficult patterns of friendship. Azerbaijan’s thriving strategic partnership with Iran’s arch-enemy, Israel, is naturally perceived as a major threat in Tehran, as it fears greater Israeli presence in its northern backyard. In March, in a joint press conference with his Azerbaijani counterpart, Israel’s foreign minister announced that Tel Aviv and Baku would “build a united front” against Iran. Israel has also occasionally supported independence for “Southern Azerbaijan”. Conversely, the historically close ties between Iran and Armenia, and their economic and diplomatic developments in recent years, including Tehran’s political and military support for Yerevan, are a huge thorn in the side for Baku.

Importantly, Azerbaijan and Iran had relatively stable relations until the 2020 war, since when Iran has been sidelined. An important regional goal for Iran is to keep foreign (primarily western) and Turkish presence out of the South Caucasus. Much of Baku’s foreign policy is at odds with this aim, notably its growing links with the West – including its energy trade and the EU’s mediator role. Moreover, as Russia’s power in the region diminishes, the West’s and Türkiye’s increase. Iran has traditionally viewed the South Caucasus states as mostly lacking agency and part of Moscow’s ‘sphere of influence’, perceiving Russia as a barrier to foreign interference.

Another major bone of contention is Baku’s Zangezur corridor ambitions. Like Yerevan, Tehran is strictly opposed to this for many reasons linked to its geopolitical, economic and strategic interests. The corridor would cut Iran’s narrow (40 kilometres) but crucial land access to its partner, Armenia, and allow Azerbaijan to bypass Iran to reach Nakhchivan.[14] This would reduce Iran’s transit options and regional involvement and increase Azerbaijan’s and Türkiye’s control of regional trade routes. This, in turn, would increase Tehran’s dependence on Baku and Ankara, and reduce Tehran’s, and increase Baku’s and Ankara’s ability to project power in the South Caucasus. It would also promote Turkish influence in the South Caucasus and beyond to Central Asia, in line with Türkiye’s pan-Turkish ambitions, but to the detriment of Iran.

Thus, Tehran has fiercely opposed such plans in both rhetoric and action. Tehran has frequently reiterated that changing internationally recognized borders in the region is a red line. Iran’s ambassador to Armenia emphasized in February 2023 that, “[…] Iran and Armenia will not allow the creation of such corridor”. Iran has also clearly underlined its message with large-scale military exercises near the border with Azerbaijan in both 2022 and 2021. Iran opened a consulate general in Armenia’s vulnerable southern Syunik region in October 2022, and it has recently established an Armenia-Iran free trade zone. Even though Iran has frequently and recently expressed support for Azerbaijan retaking lost territories, a victorious, assertive Azerbaijan, free from Russian dominance and in a military-security triad with Türkiye and Israel could be a dangerous prospect for Tehran.

Against the backdrop of these increasing geopolitical rivalries, Azerbaijan and Iran have witnessed sharply growing tensions and hostility in recent years. These include: military drills by both sides; verbal escalation and threatening rhetoric; arrests of alleged spies; diplomatic expulsions; and controversial incidents such as the January 2023 fatal attack on the Azerbaijani embassy in Tehran, and the March 2023 shooting of an Azerbaijani parliamentarian. This has led many to speak of a looming critical breaking point in relations if trends continued.

However, the two countries have recently tried to limit tensions through diplomacy at different levels. The July 2023 visit to Baku by Iran’s Foreign Minister Amir-Abdollahian, including a meeting with Aliyev, marked a turning point towards an emerging thaw and normalization of relations. In an attempt to soothe Tehran, Aliyev reiterated the promise that “Azerbaijan will never allow a threat to […] Iran from its soil”.

This, combined with other deterrent factors, which include Azerbaijan’s dependence on Iranian territory to reach Nakhchivan; clear US support to Azerbaijan vis-à-vis Iran; mutual relations with Russia and Türkiye; and Iran’s vulnerability due to its political and economic instability, prevent tensions from escalating beyond control into worse scenarios. It is also unclear whether Iran would risk a full-scale conflict with Azerbaijan in order to protect Armenia – although there are other options for Tehran.

Nonetheless, tensions and uncertainty are likely to remain. Azerbaijani-Israeli ties will continue to grow, and Baku’s desires of a Zangezur corridor are unlikely to disappear. Regional power dynamics will continue to shift in Baku’s favour and against Tehran, not least greater Turkish and Western and reduced Russian capacity. As Azerbaijan’s confidence, might and manoeuvrability increase, Iran’s influence and options are decreasing. The increasing clout of the hardliners in Iran’s government mean that mutually high threat perceptions, geopolitical competition, mistrust and security concerns are all likely to remain in place.

Conclusions: An Uncertain Future for Azerbaijan and the South Caucasus

An Unclear Path for Azerbaijan’s Identity

A central question for Azerbaijan is about the ongoing (re-)construction of its identity. For almost 30 years, since the First Karabakh war, Azerbaijan’s foreign and domestic policy focus was on the goal of retaking Nagorno-Karabakh, thereby restoring a perceived historical injustice and the country’s territorial integrity. This was the foundation for Baku’s geopolitical strategies and the pillar of its national identity, and here the government and the population were in total sync.

Now, having finally achieved its goal, there is considerable uncertainty over how Azerbaijan’s politics, nationalism and identity should be reconstituted. Moreover, recapturing Nagorno-Karabakh has not resolved any of the multiple enduring economic and socio-economic issues facing the country, such as inequality, oil dependency, water scarcity and societal discontent, against a background of growing political repression and disappearing civil society space. The liberation of Nagorno-Karabakh was an immensely popular achievement by the government, but its rally-around-the-flag effect, and function as a distraction, could now potentially start to diminish.

Therefore, a vital question is through which new ideas and narratives the regime should mobilize popular support and uphold its legitimacy. Ideas include a return of Azerbaijanis to Karabakh, “Western Azerbaijan” in Armenia’s southern Syunik province (“Zangezur”), “Southern Azerbaijan” in northern Iran or cementing an eternal “victor” attitude towards the archnemesis Armenia. Here, it is arguable that Azerbaijan’s ontological security – the country’s secure and stable self-identity, bolstered by autobiographical narratives and routinized relations with others – could be challenged, as its relations with its main “Other”, Armenia, against which it understands itself, is still deeply uncertain.

Uncertainty and Manoeuvrability Between Different Geopolitical Variables

For Baku, the two dimensions governing its geopolitical situation are uncertainty and manoeuvrability. Despite many stabilizing factors – its consolidated authoritarian rule, its military might, its growing geopolitical clout and its relative economic stability – Azerbaijan faces considerable uncertainty and complexity based on the challenges from different interconnected factors. This level of unpredictability and entanglement, and how different variables both restrain and enable Baku’s foreign policy goals and options, is underappreciated in Western analysis and understanding of Azerbaijan. It also has stark policy implications for the EU’s options and ambitions in the South Caucasus.

The perhaps central variable that generates both uncertainty and manoeuvrability for Azerbaijan is the ongoing shifts in geopolitical dynamics and power balance in the South Caucasus. Uncertainty stems from how Baku might consolidate its growing position, manoeuvre use of its leverage vis-à-vis other actors and realize its potential as a central energy and connectivity hub. Questions here include how assertive Baku can be towards Moscow and Tehran, partly based on how they will deal with their increasing dependence on Baku; and, relatedly, how much backing Baku will get from Türkiye and Israel. Connected unpredictable elements are how developments in Ukraine will affect Moscow’s influence in the South Caucasus and how relations will develop within the regional triad of Russia, Iran and Türkiye.

Another crucial factor is the relationship with Armenia. While Baku may in effect have forced a solution to the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh, many questions remain, including the fate of Karabakh Armenians and how Baku can use its military capacity and confidence to consolidate gains and reach other potential goals, for example on the Zangezur corridor. Baku’s room for manoeuvre here also depends on the stances and efforts of Russia and the EU.

Yet another unsettled parameter is Azerbaijan’s relations with the EU. The central issue here for Baku is how to maintain vital economic ties – especially hydrocarbon exports – and push for its vision of peace in mediation efforts while balancing difficult political links. This will depend on several thorny components, such as EU actions and (dis)unity in its approach to Baku and support for Armenia; and the amount of political will and resources the EU is willing to spend on bolstering its regional influence.

Another source of uncertainty for Azerbaijan is the ongoing Israel-Hamas war and increasing tensions in the Middle East. As anti-Israel sentiment increases and pro-Palestinian support is mobilized across the Middle East and the developing world, Baku might find its position increasingly difficult to navigate between close relations with Tel Aviv and efforts to promote a leading role in the Muslim world. This is also exacerbated by the fact that Azerbaijan’s closest ally, Türkiye, has strongly positioned itself in support of Palestine and harshly criticized Israel, exacerbating tensions between Ankara and Tel Aviv. Important questions for Baku therefore include how to leverage and capitalize on its crucial ties with both Türkiye and Israel; and whether Ankara will pressure Azerbaijan to reconsider its relations with Tel Aviv as a quid pro quo.

All these variables therefore engender both uncertainty and room for manoeuvre for Azerbaijan, at the same time, and in relation to each other. Both constrained and empowered by this intricate web of interdependent relationships, Baku must navigate and balance between its various non-aligned foreign policy goals and options.

Policy Recommendations for the EU

Importantly, we do not know exactly how Baku will balance between these different complex variables, or how it will navigate the uncertainties and room for manoeuvre. Nor do we know how this complex interplay between regional variables will develop. The EU’s policy vis-à-vis Azerbaijan and the region must necessarily reflect this complexity and uncertainty. The EU must therefore be strategic, calculated and balanced in its approach, taking account of how its policies will affect and be affected by the various variables. While the EU has significant economic and political leverage over Baku, it is also dependent on Azerbaijan for many of its goals in the South Caucasus. Moreover, the EU’s role in the South Caucasus is especially important given the strategic disengagement from the region of the US.

- The EU’s policies on Azerbaijan should be integrated into a broader framework. Together with its approach to Armenia, these policies must form a holistic and comprehensive regional strategy on the South Caucasus, including on countering Russia. This policy framework should also be in alignment with the EU’s wider policies on the Eastern neighbourhood, and ultimately interconnected with its policies on Iran, Türkiye, and Central Asia. The EU policies vis-à-vis Baku and Yerevan must therefore be considered, designed and implemented proactively with the view of reaching the EU’s regional goals, including peace and normalization; stability and democracy; development of regional trade and transit routes; increased EU influence; and isolation and containment of Russia.

- The EU should constructively and actively encourage Baku and Yerevan to formulate and pursue desirable goals. Currently, in this new and highly uncertain situation, both Azerbaijan and Armenia stand at a crossroads. They can continue down the path of hostilities, aggression, revanchism and obstruction, or choose the route leading to mutually acceptable peaceful coexistence. The EU has the opportunity to influence their decisions through strategic engagement and cooperation with both.

- While sending clear messages to Baku on the EU’s red lines on Azerbaijani military aggression against Armenia, the EU must also work strategically to avoid alienating Baku. To retain its credibility and possibility to act as a peace mediator trusted by both sides, the EU needs both internal unity, and active buy-in from both Yerevan and Baku. The EU-led peace process is the strongest long-term prospect for peace, stability and prosperity in the South Caucasus.

- While increasing cooperation with Azerbaijan in the energy, renewables, connectivity and transit areas, the EU must also call out and pressure Azerbaijan on its growing internal repression and human rights abuses. Furthermore, energy and transit cooperation with Baku must not be a way to enable Russian sanctions-busting.

- Thus, while providing support for Armenia’s security, resilience and pro-democracy and pro-European path, the EU must also work strategically to improve cooperation with Azerbaijan in relevant areas beyond trade and energy, such as demining, rehabilitation, gender issues, people-to-people contact and civil society support and cooperation. Improving bilateral cooperation and relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as multilateral cooperation through the Eastern Partnership and potentially other regional formats, will increase the EU’s regional influence and the prospects for peace.

Striking the right balance between these various policy objectives will be exceptionally challenging, especially in the light of the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape. This also requires deeper understanding of both Azerbaijan and Armenia, including their respective motives, concerns, and options, as well as of the prevailing issues and the trends shaping geopolitical developments in the South Caucasus. Consequently, the EU must be both careful and agile in its policies.

Notes

[1] “Zangezur” is a historical name for the area used by both sides.

[2] Azerbaijan has occupied more than 200 km2 of Armenian territory since 2020 without facing any international pushback.

[3] Stepanakert in Armenian.

[4] All trade data in this report is from the UN Comtrade database, based on Azerbaijan as the reporting country.

[5] Although Azerbaijan was never part of the Ottoman empire, and Türkiye had very little contact with the Azerbaijani SSR during Soviet times.

[6] The trade data in this section is based on the UN Comtrade database and the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade’s reporting. Unfortunately, gas exports are often not properly accounted for in customs data. The 2022 data for Azerbaijani exports may therefore vary as gas exports heavily increased.

[7] The top partners are Germany (5% of all Azerbaijani imports 2018–2022), Italy (3%), France (2%), the Netherlands (1%), and Poland (1%). The top products imported from the EU are machinery, transport equipment, chemicals, foodstuffs, base metals, clothes, plastics and live animals.

[8] Although Aliyev was also in Kyiv in January 2022, signing agreements on bilateral cooperation and declaring his support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

[9] Whether Armenia is slowly withdrawing from the CSTO or not is difficult to say.

[10] One important example is the extensive Russian military presence in Armenia.

[11] The two countries have clearly signalled support for each other’s territorial integrity, which also reflected Baku’s wish to emphasize the parallels with the internationally recognized status of Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani.

[12] Like other post-Soviet states, and as enshrined in article 18 of its constitution, Azerbaijan is a secular state, and considered one of the most secular Muslim countries in the world. Baku has also recently increased its crackdown on Shiite Muslims.

[13] The exact number is unknown, and varies widely, according to different sources, between 12 and 25+ million.

[14] In nationalist Iranian spheres, this also triggers national memories of losing control over Caucasus territories to Russia in the wars of the 19th century.